Unit

8: Contemporary Cherokee Art in Oklahoma

(1900- 2006)

|

|

Introduction:

The following

lesson plans, by Dr. Mary Jo Watson, are designed to provide students

with an understanding of contemporary Cherokee art. This includes

four artistic art forms, basket weaving, pottery, painting and sculpture.

For centuries

objects of great beauty were made to use in spiritual ceremonies

and the same careful attention was given to items used in everyday

life. A well developed set of conventions and aesthetics are a long-standing

tradition among all Indian nations including the Cherokees. Early

explorer-artists, later, naturalists and historians noted the fine

craftsmanship of the Cherokees. This included weaving mats and baskets,

jewelry making, pottery, body ornamentation, careful attention to

clothing and dressing hair. Construction of housing and forms of

weapons required skilled hand and eye coordination. Exuberant expressions

were found in Cherokee feather work, painted house posts and a myriad

of artistic creations.

It is also important

to note that Cherokee traditions and iconography are found in contemporary

arts even though materials and the resulting forms in many cases

are very different than that of the ancestors. Even though Cherokee

arts and culture are dynamic, the artists maintain ideas that reach

back for several millennia. This is explained in the information

following.

Contents:

Lesson

1: Understanding Indigenous Arts of the Americas

Lesson 2: Basketry

Lesson 3: Pottery

Lesson 4: Carving and Sculpture

Lesson 5: Painting

Guiding Questions:

- How do

the contemporary Cherokee artists honor their artistic and spiritual

traditions in their arts? What are some of the older forms of

Cherokee art?

- What are

the new materials and forms that are now prevalent in Cherokee

arts?

Learning

Objectives

After completing

this lesson, students will:

- Be able

to recognize and describe four forms of Cherokee art

- Be able

to discuss the specific meaning of four traditional art forms.

- Be able

to discuss how the Cherokee artists have incorporated contemporary

styles, and materials in four art forms.

Lesson

1: Understanding Indigenous Arts of the Americas

What are some

of the Indigenous arts of the Americas? Do you know about the pre-contact

art (prior to 1492), of the Southeastern Seaboard of the United

States? Within the past several years, scholars including historians,

anthropologists, and art historians turned their attention to the

Indians of the Southeast. Thirty years ago, historian Charles Hudson

stated that, “the native people of the American South—the

Southeastern Indians possessed the richest culture of any of the

native people north of Mexico.” (Hudson p. 3) This includes

the arts of the Cherokees among others. De Soto saw architecture

and artistic forms that he described as exceptional, though many

are now lost. The early travelers into the Southeast including William

Bartram (Hudson, 1976, p. 380), described the visual arts, including

paintings, wood carvings, body ornamentation, pottery, basket making

and jewelry.

Art historians

are currently involved in developing a new understanding of all

Indian art forms using a multi-disciplinary view including history

and anthropology. An equally important aspect of investigation is

speaking to the elders and spiritual leaders of tribal areas and

stomp-dance grounds to gain valuable insight into Southeastern Indian

beliefs. It is now recognized that the early arts “an outward

expression of their belief system” and that the arts were

used in relationship to music, dance and story telling (Thornton

1990, p. 10). Understanding the beliefs and values held by the early

Cherokees provides a basis for our study and appreciation of the

traditional icons (images) found in many contemporary Cherokee art

works.

The Cherokees

were originally located in the valleys of the southern Appalachians

and some archaeologists believe they were growing corn about A.D.

1000 and that the, “ancestral mother Selu have given them

corn on which they depended for subsistence.” (Perdue, p.

14.) From that time forward and into the Twentieth Century it was

primarily the role of women to maintain the fields, prepare the

food and care for the young. All creative work of that time, now

regarded as art, was gender specific. Women wove mats and baskets

which came in various sizes, some baskets nested one into another.

They used split river cane with both natural color and dyes made

from walnut hulls, berries and various roots. Women made cooking

vessels of clay, including pots, cups, pitchers, and platters. Women

sewed deer skins with bone awls into clothing and pouches woven

with buffalo hair. Men constructed houses, and spent a good part

of each year preparing weapons for the long, hard hunting season.

Carving was the prevue of men, and they whitewashed their homes

and painted on door posts. In 1775 James Adair (trader and historian)

noted the fine quality of wooden stools, storage chests, booger

masks, bowls spoons and dugout canoes all carved by Cherokee men

(Leftwich p. 87-92).

The Southeastern

Indian belief system is complex and shaded by the ensuing centuries.

Anthropologists and historians have determined however that the

system was one in which order and balance was sought after between

three realms.

“Southeastern

Indians perceived the world as having three realms: an Upper World

and Underworld, which existed initially, followed later by This

World. Each realm of the three-layered cosmos was occupied by

specific beings and associated with particular concepts of time

and symbolic values. The world and everything in it (even anomalies)

fit within an orderly, although complex. pattern of existence

and meaning, as expounded by Charles Hudson (1970):

In the Upper

World, things existed in a grander and more pure form than

they did in This World. For example, animals in the Upper World

were much larger than animals existing in This World. In contrast,

beings in the

Underworld were ghosts, monsters, or creatures with inverted properties.

The seasons in the Underworld were just the opposite of seasons

in This World. Beings in the Underworld sometimes were rattlesnakes

about their necks and wrists, a grisly inversion of the custom

of wearing necklaces and bracelets in This World.

Art representing

This World included realistic human portraits, objects that verified

the chief’s authority, (maces and celts), and other items

underscoring leadership status (gorgets with litter symbols),

as well as abstract worldly symbols such as the cross, cross-in-circle,

swastika, and circles of various designs” (Susan Powers

163-180).

The Upper World

contain symbols rayed circle, rainbow, bilobed arrow, hand and eye,

hand and arm bones were depicted on shell engravings and some images

are found on pottery. The sun circles and bird imagery are also

found with the Upper World.

Artistic images

of The Underworld include water dwelling beings, fish, snakes, and

Uktena, a Cherokee underwater monster who has a serpent body with

wings and deer horns on its head. Another Cherokee mythological

figure of The Underworld is Tlanuwa, a monstrous bird of prey. (Powers

173-4)

According to

Hudson, “The Upper World epitomized order and expendableness,

while the Under World epitomized disorder and change, and This World

stood somewhere between perfect order and complete chaos.”

(P. 123-125) Complex levels of ideology and corresponding iconography

represent each of these worlds, and each held specific meanings.

Symbols and signs of the Cherokees are replete with images from

the earlier Southeastern mound cultures. Pottery designs include

curvilineal swirls, birds and the cross and circle motifs. Images

of falcons, turkeys, eagles and anthropomorphic creatures such as

a winged-serpent are also present in the older arts. These are but

a few of the symbols and concepts we can now discern from the early

peoples.(Phillips and Phillips pp.146, 156. 1978). All humans had

a role to play in the stability of the world, but at this point

in time our interpretations are limited by our lack of deep understanding

(Hudson. pp. 120-183). These beliefs and concepts were present in

the early years of European incursion and many of the same iconography

and motifs are present in current art forms of the Cherokees.

After European contact new materials such as cloth, metal tools

and commercial paints brought about changes in Cherokee arts. This

was in conjunction with an adaptation to some changes in their life

including the acceptance of some of Christianity. After valiant

resistance over a long period of time, thirteen different groups

of Cherokees were removed from their southeastern homelands. Thousands

of tribal members endured the agonies of removal and were settled

in eastern Oklahoma during the Nineteenth Century(Conley p. 156).

By the beginning of the Twentieth Century there were 35,000 Cherokees

in Indian Territory ( Thornton, p. 116.)

The well established

canons of artistic traditions were in place early on by Cherokee

people using local materials, and exerting ingenuity to make things

of beauty and for practical use. Later, after removal, like most

Indians in the Twentieth Century, the Cherokees had mastered Euro-American

media in all areas of the “arts.” This includes the

use of oils, watercolors and later acrylic paints. Wood sculpture

continued and cast bronze was employed by Cherokee artists. New

materials found in eastern Oklahoma for weaving baskets and other

new fiber materials were added to Cherokee creative expressions.

Even now, although not part of this discussion, the latest works

in art by Cherokees artists are found in film, digital photography

and various electronic media.

The ability

of the Indian Nations and, importantly, the Cherokees to incorporate

and facilitate new materials and forms into their arts is the focus

of the artists presented here. The resistance to complete change

and the continuation of thousands of years of development and creative

designs and motifs are present in the art of Cherokees in the 20th

and 21st century. This is remarkable. A sense of continuity, a belief

in ‘the people,’ as a united community is observed in

the works of contemporary artists. The imagination of the people

called the ‘Cherokees’ is a marker made of their tenacity

and spirit.

Lesson 2: Basketry

Textual

Sources for Baskets

Rodney L.

Leftwich. Arts and Crafts of the Cherokee. Cherokee, North Carolina:

Cherokee Publications, 1970. pp.

9-51. Permission to use pages 21-51 granted by Cherokee Publications.

The complete text and a wide wide variety of Cherokee and Native

American books can be ordered from online or by requesting a free

catalog. Cherokee Publications, PO Box 430, Cherokee, NC, 28719.

http://www.Cherokeepublications.net

800-948-3161

Tsalagi Basketry. Plants, History

http://www.kstrom.net/isk/art/basket/baskcher.html

James Mooney.

Myths of the Cherokees. New York: Dover Publications, 1995.”How

the World Was Made.” p. 240

http://www.sacred-texts.com/nam/cher/motc/motc001.htm

“For more

than a thousand years, women wove an astonishing array of baskets

and mats for scores of uses. They made them for exchange with friends,

neighbors, and strangers, for food gathering, processing, serving,

and storage, and to utilize in ceremonials and rituals. They kept

ceremonial objects and medicinal goods in baskets. They covered

ceremonial grounds, seats, floors, and walls with mats. They concealed

and protected household items and community valuables in baskets.

Basketry was central to women’s activities and to Cherokee

society.

Early European

writers consistently identified basketry with women, ‘the

chief, if not the only manufacturers.’ The association of

women with basketry is one of the more enduring aspects of Cherokee

culture. Woven goods----baskets and mats----document what women

did, when, and how. They illuminate the work of women who transformed

the environments that produced materials for basketry. They point

to women’s roles in ceremonial, subsistence, and exchange

systems. As objects created and utilized by women, baskets and mats

conserved and conveyed their concepts, ideas, experience and expertise.

They assert women’s cultural identity and reflected their

values.” (Sara H. Hill. Weaving New Worlds. pp. 37-38.1997).

Basket making continued among the Five Tribes after removal into

Oklahoma, the Cherokees and Choctaws maintaining the strongest link

to this traditional form of women’s art. Materials used by

the Oklahoma Cherokees included buck brush, blackjack, post oak

and honeysuckle. Black walnut and bloodroot were the most common

materials used for dyes. Although women have used commercial dyes

for some time, many prefer traditional use of local dyes.

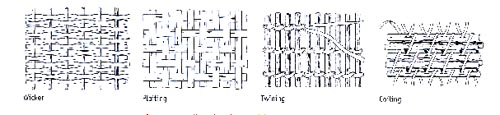

There are three

basic weaving techniques used by Americans Indians, coiling, twining,

and plaiting, and the last is used consistently by the Cherokees.

Techniques used in plaiting are checker work, twill and wicker.

Bruce Bernstein.

The Language of Native American Baskets. Washington: Smithsonian

Institution, National Museum of the American Indian, 2003. P.14.

Perhaps the

most recognizable technique used by both eastern and western Cherokees

are the double wall baskets. An inner wall is woven from the bottom

up; then the spokes are folded over and the outer wall is woven

down and the finished basket has two walls of equal quality.

Bessie Russell –Basket Weaver–Cherokee

Nation-Rose, Oklahoma. Bessie Russell was declared a Cherokee National

Living Treasure and Master Craftsperson in 1998. She studied under

the Cherokee weaver Thelma Forest in 1975. Russell uses honeysuckle

reed to make her baskets and dyes from walnuts, bloodroot, poke

salad berries and plums. Basketry utilizes materials from the artists’

surrounding environment. Forms of her baskets include the turtle

and pumpkin shaped baskets and she also makes arrow quiver baskets.

Bessie Russell is a Cherokee speaker.

Questions

for Analysis

Ask the students

to be able to explain why basket weaving is a symbol of strength

and courage for the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma. How has the Cherokee

Nation recognized this art form at the present time?

Have the students

discuss the different ways that baskets are made and discuss some

unique qualities found in Cherokee basket making. (Cherokee Publications

has made available a selection of Leftwich’s Arts and

Crafts of the Cherokee for this lesson plan.)

Refer back to

the quotation from Sara Hill above. Ask the students to think and

reflect on the ideas that she presents in this statement. Baskets

were an expression of much more than a simple woven product. Have

students discuss the meanings and Cherokee designs. (A useful website

for these purposes is Cherokeebaskets.com; see below.)

Lesson 3: Pottery

Textural

Sources

The Cherokee

Nation Tahlequah, Oklahoma http://www.cherokee.org

“The

Cherokee Phoenix” VOL, xxv, No. 2 - Spring 2001 Story and

Photo by Will Chavez Staff writer. A story about Anna Belle Sixkiller

Mitchell, potter -- a person declared a “national treasure”

by the Cherokee Nation.

(Article

on Anna Belle Sixkiller Mitchell.

There is considerable

evidence of the flourishing pottery industry throughout the ancient

southeastern United States. From Virginia through the Florida Keys,

from across the south into Arkansas and Oklahoma, vessels manufactured

by prehistoric Indians demonstrate a high developed art form.

In the eighteenth

century James Adair commented on Cherokee pottery making:

They make

earthen pots of very different sizes, so as to contain

from two to ten gallons; large pitchers to carry water; bowls,

dishes, platters, basins, and a prodigious number of other vessels

of such antiquated forms, as would be tedious to describe, and

impossible to name. (Adair, History of the American Indians.)

Cherokee and

most Southeastern pottery was usually formed by coiling. This process

involved gathering and processing clay, making a flat-clay base

and laying long coils of clay wound in a circle one upon another

until the desired height was reached. Walls or sides were continually

smoothed by hand and by paddling with a wooden tool to keep an evenness

on the vessel walls. Designs were applied by hand or with carved

wooden stamping paddles. The clay was then fired. Pottery continued

on a limited basis in Oklahoma through out the early years of the

Twentieth Century. The revival of pottery making commences in the

second half of the twentieth century and the premier Cherokee leader

is Anna Belle Sixkiller Mitchell. (Read the story about Anna Belle

in the Cherokee Phoenix-web page listed above).

Like many Oklahoma

Indian artists, especially women, Anna Belle did not turn to the

study of tribal culture and pottery until after she raised her children.

She traveled to museums searching for Cherokee pottery and examples

of how they were made. Over a period of time she became familiar

with the older Southeastern Indian pottery and began creating pots

that have won national and international acclaim. She uses designs

found in nature including, birds, human figures, animals, reptiles

and plant life, similar to those found on pots throughout the southeast.

She went beyond the Southeast and studied the pre-contact work of

the ancient Indians in the Hopewell area in the Northeastern United

States and the Quapaws of Arkansas. Many of her pre-contact designs

include scrolls, interlocking squares, representing the four cardinal

points, falcon, eagle, sun circles and many bird effigy pots.

Although pottery

was one of the most diminished forms of American Indian art in the

late part of the 19th and early part of the 20th Centuries, Oklahoma

and the Cherokees in particular are experiencing a revival of pottery

in the 21st century. Many of the potters are expressing the ancient

designs of their ancestors of the Southeast and are accomplished

with their individual creative ideas. Other important Cherokee potters

include, Crystal Hanna, Jane Osti, Bill Glass, Demos Glass, Victoria

Mitchell to name only a few.

Questions

for Analysis:

Ask the students

to discuss why making pottery would be important to Cherokee artists.

Why would the continue to use ancient designs? Why would Anna Belle

Mitchell say, “ I believe without art you don’t have

culture and without culture you don’t have art.”?

Using the websites

below that are devoted to pottery by various Cherokee artists, divide

the class into groups and ask them to produce reports on the similarities

and differences within pottery artists and, then, to note the design

features that basketry and pottery might share.

Divide the

class into groups. Ask the different groups to think of ways that

their own culture is represented by objects or items. (This could

be something as simplistic as the idea of jeans and tennis shoes)

Clothing, music, films, Ipods, and numerous other examples are all

symbols of contemporary culture. Explore some works on Cherokee

art and some websites on Cherokee art: what might be corresponding

objects or items in Cherokee culture that would “match”

similar objects in other cultures?

Ask the students

to relate their culture of arts and beliefs and how it defines their

identity.

Lesson

4: Carving/Sculpture

Textural

Sources

Rodney L. Leftwich.

Arts and Crafts of the Cherokee. Cherokee, North Carolina:

Cherokee Publications, 1970. PP. 87-107

An article from

the Cherokee Phoenix, xxv, 2, Spring 2002, Arts and Culture section

on Sam Watts-Kidd who art work is displayed at the Cherokee Heritage

Center and helps to structure the Trail of Tears exhibit. A .pdf

file through this website.

Woodcarving and sculpture were observed in the Southeast in the

early reports by Europeans. Members of the de Soto expedition saw

a building filled with wooden statuary. (Hudson, p. 380) Many of

the wooden items decayed but examples can be found from the Key

Marco site in Florida and from the Spiro Mounds in Oklahoma. Following

their ancestors, the Cherokees made numerous carved hunting tools

including bows and arrows, clubs, lances and cane and reed knives.

(Swanton p. 564). Wooden stools, dishes, spoons, platters, trays,

scratchers, and dugout canoes were part of the wood carved objects.

The Eastern Cherokees and those removed into Oklahoma were surrounded

by forests and different types of wood with which to carve. In eastern

Oklahoma wood workers have a broad choice of walnut, red cedar,

wild cherry, Catalpa, and Sassafra among other types of wood.

One of Oklahoma’s

greatest Cherokee artists is Willard Stone. (1916-1985). “Stone

has been a major force in Indian sculpture since 1940. He has perfected

a smooth, rounded, wood sculpting style that has come to be recognized

as a regional style unique to Oklahoma.” (Archuleta and Strickland,

p. 96.) His subjects included children, mothers, animals birds,

buffalo and Indian themes. He was always drawing and painting but

as a teenager he suffered a serious injury that almost ended his

artistic career. He picked up an odd object that was a dynamite

cap that blew off most of three fingers on his right hand and damaged

his face and chest. A plastic surgeon repaired his face and chest

but his fingers were inoperable. Eventually he commenced working

in wet clay and he found that he could make figures with only partial

fingers. He was encouraged by the famous Oklahoman Grant Foreman

and later by the Tulsa oilman Thomas Gilcrease.

Three of his

most reknowned pieces refer to the Trail of Tears and the Removal.

One, now located at the Cherokee Heritage Center in Tahlequah, is

titled “Exodus.” This elegant work refers to the removal

of Cherokees form their homes in the Southeast and all of life’s

journey. Following is Stone’s comment concerning this special

piece of sculpture.

“Over

a trail of tears, reaching from the Great Smoky Mountains in North

Carolina, Georgia and Tennessee to eastern Oklahoma, the Cherokees

West were uprooted, transferred and transplanted in our present

state. In this block of native walnut, from a tree, older perhaps

than the time of removal, I have tried to capture the tragedy and

heavy load of sorrow and heartache being overcome by the Cherokee’s

courage and determination. I have tried to boil down and bring into

focus the heavy load of life the whole of mankind carries—and

put it into an individual mother and child. The design is composed

of two large teardrops, one balancing the other, on a base representing

the contour of the earth—for each individual’s trail

as he carries his load through a lifetime. One teardrop is composed

of his courage and determination to survive in his search for happiness;

the other is representative of the heavy load of love in his heart

and on his back, that he willingly carries in his short time on

his long trail.” (Hamilton and Stone p. 71) (see: http://www.willardstonemuseum.com/exodus.htm)

This image was

created in 1967 and is 18" x 32" x 61/2" and is made

of Walnut with some limited bronze.

Questions

for Analysis

Ask the students

to read Stone’s statement about his work which is quoted above.

See if they notice the shift from the tragedy of removal, to the

struggles of life that he references with this work. This work represents

to Stone more than removal–it is a lesson about the struggle

of all human life during our time on earth.

Ask the students

to research the work of Willard Stone on the web. See if they can

find rabbits, great Cherokee Chiefs, or children that were carved

by Stone. Ask them to talk about the image and their reactions to

the piece.

Ideas

for those interested in learning more:

Leftwich’s

work is out of print, but it is available through library lending

systems and Cherokee Publications is planning an updated version.

He traces the development of Cherokee wood-carving from colonial

contact days to the mid-20th Century. The carving ranges over canoes,

outdoor games, representations of animals, and of human garb. Wood

carving was largely a male activity. Find this book, do some reading,

and research wood carving in the Cherokee. Does this tell you anything

about how Cherokee men have thought of themselves or can you describe

what a Cherokee man “sees” as beautiful (or ugly)? Take

into account Stone’s work as well.

Lesson

5: Painting

Textural

Sources

“My

Version of Reality: An Interview with Dorothy Sullivan”

http://www.ahalenia.com/id/id%20ten/dorothy.html

“Cherokee Artists: Museums, Galleries, and Artists’

Organizations”

http://ahalenia.com/noksi/artists.html

These two

important web sites are provided by the well-known Cherokee artist

America Meredith. I am indebted to her for her continual work

to keep the Cherokee artists’ and the Cherokee Nation in

the forefront.

To see the

art of American Meredith go to: http://www.ahalenia.com/america/

There are several other links that she has provided which details

her and other Cherokee artists’ work.

As the twentieth

century opened the arts of the Cherokee were continuing along traditional

lines, however changes were occurring. Indian students, including

those inclined toward the arts were slowing beginning to combine

the traditions of the ancestors with new media and materials including

painting. Cherokee men and women had long been concerned with shape,

form, line and color. As stated above, their aesthetics standards

of fine quality, and superior hand and eye coordination were directed

into new areas of expressive art. An outstanding example of a Cherokee

artist who was a pioneer into the new areas of possibilities of

the twentieth century was Cecil Dick. (1915-1992).

“As a

small child Dick spoke only Cherokee. ‘Orphaned at 12 and

reared in Indian boarding schools, the artist became an authority

on Cherokee mythology and the Cherokee written language.”

(Snodgrass 1968 quoted in Lester 1995, p. 151.) Dick spanned the

century and included in one of his paintings a traditional Southeastern

Warrior in the forefront on the picture plane with a rocket ship

blasting off into space in the back ground. He received great honors

during his lifetime for his art work which was singularly focused

on “the Woodlands,” or Southeastern Indian style. This

style is recognized by the use of the mound culture symbols, traditional

dress of the Cherokees, and themes that reflected the life of Southeastern

Indians. (For examples, see websites cited below.)

After World

War II the surge of returning Indian veterans and the numbers of

Indian students in art schools accelerated. The Philbrook Museum

in Tulsa, Oklahoma opened an ‘Indian Annual,’ where

Oklahoma and national Indian painters, potters, weavers and sculptors

could be recognized with prestigious awards for their fine works.

Many Cherokees were included in the group of top artists. During

the last half of the twentieth century some of the important painters

of the Cherokee Nation include Joan Hill, who has won over 250 national

and international awards and is perhaps the best known Cherokee

painter. Others include the late Talmage Davis, Troy Anderson, Brooks

Henson and America Meredith to name a few. Their styles are different

yet all reflect a Southeastern bent including that of the Dorothy

Sullivan.

The work of

Dorothy Sullivan, however, has a curious and unusual look and style

and is described by some as ‘post-modern.’ Her dedication

to reality, to the truth about Cherokee life and her own family

history is rife throughout her paintings. More to the point, in

her painting Sullivan represents the quintessential artist historian,

who goes into her heritage -- family, clan and tribe -- and provides

her individual creative take on events, people and mythology.

In the interview

with America Meredith she was asked the question about proving herself

and following is her reply. “....My Dad was born in a double-log

cabin over on my grandma’s Cherokee allotment over near Stillwell

in Goingsnake District When we were growing up he always taught

us about being proud of being Cherokee. It was always something

we just took for granted. It was just part of us.” She paints

individuals of the Seven Clans of the Cherokees along with their

respective symbols. She paints contemporary family members and traces

their ancestry in portraits of the ancestors. During her career

she has received great honors from Oklahoma and across the United

States.

Mary Jo Watson,

Ph.D.

Director, School of Art

Associate Dean, College of Fine Arts

Oklahoma University

Questions for Analysis

Have the students

research the history of the Cherokees on the internet. Determine

the location of the Eastern and the Western Cherokees. Have a discussion

of the similarity of the early art styles between the two groups

and the differences.

After using

the internet or interlibrary loan to find examples of Dick’s

and Hill’s work, along with any complementary artists, define

the similarities and differences between the two (and related) artists

in what they depict, what forms/shapes or lines they use, what colors

they work in. Your research need only rely on a few examples from

each artist.

Have students

draw a chart and list the Seven Clans and their symbols. Search

the internet and any available books on artists who portray the

Cherokee clans. (For some help, see internet sources, below.)

Have a class

discussion on how the Cherokee artists have maintained tradition

art forms/concepts within the medium of painting.

Linking

the Units and Lessons Together

Robert Conley,

Unit 7, mentions Cecil Dick as an artist who was part of the reviving

interest in and authenticity of Cherokee art. Examine the poems

of Unit 7, the passages from Conley’s Mountain Windsong,

the discussion of Dick and the examples of his art that you find

through this Unit. Then, pick an artist of your choice from this

Unit and either write a paper or have a class discussion on any

of the following four sets of questions:

What role do

all arts play in cultural recovery of the Cherokee – of any

people?

What are the different roles of different arts in imitating, expressing,

or representing a people’s life?

More general

reflections which may draw on any of the materials of the lessons

are possible:

Is it reasonable for art to be “inaccurate” in its imitations,

expressions, or representations of that life? Does imitation, representation,

or expression have to be about the past or can it be about what

a people should be like? Or about what a people might be like in

the future?

Should history, politics, religion, and art (writing or pictures)

“say the same thing” about a people? Or, should they

speak differently? What have you found when you reflect back on

two or more Units’ materials? Are the writers, artists, historians,

lecturers, teachers and others saying different or the same things?

Can you find reasons for any differences without necessarily finally

concluding someone must be “wrong”? Are there other

cases where you think somebody definitely is wrong or right?

The Cherokee Heritage Center was placed on the site of the first

Women’s Seminary and three columns from that building still

stand on the site. The Center holds classes for both Cherokee and

people who are not Cherokee. It is a museum, also, which shows exhibits

of Cherokee life before, during, and well after the Trail of Tears.

It is also a museum which introduces people to contemporary Cherokee

art. Do you think education is important to the Cherokee? If so,

why – site from the various Units to prove your point. Do

you think there is a link between art, education, and culture? Site

from the various units to prove your points.

Internet

Sources

Many of the

sites online are commercial to varying degrees. They do, however,

provide valuable examples of materials, weaving processes, types

of baskets, types of design in basketry, pottery, and painting.

In addition to the sites listed within Mary Jo Watson’s lecture,

ACTC offers the following for further examples of art and artists.

If you use these in your research, consult with your teacher.

General:

http://www.cherokeeartistsassociation.org/index3.html

This site has been formed to display and protect the work of contemporary

Cherokee artists. Viewers will find basketry, sculpture, pottery,

and painting examples of contemporary art. Many of the artists discussed

by Mary Jo Watson have their work displayed at this website.

Basketry:

Most sites will

illustrate the double-walled baskets discussed above, by Watson.

Rodney L. Leftwich.

Arts and Crafts of the Cherokee. Cherokee, North Carolina: Cherokee

Publications, 1970. pp.

9-51. Permission to use pages 21-51 granted by Cherokee Publications.

The complete text and a wide wide variety of Cherokee and Native

American books can be ordered from online or by requesting a free

catalog. Cherokee Publications, PO Box 430, Cherokee, NC, 28719.

http://www.Cherokeepublications.net

800-948-3161

http://www.cherokeebaskets.com/index.htm

A useful site that gives examples of Cherokee basket types, weaves,

and cane materials also discussed in Leftwich. Copyright must be

honored to use articles.

http://www.kstrom.net/isk/art/basket/baskcher.html

A quick overview of weaving, particularly the large burden baskets,

in the area around Asheville, NC. Cited by Watson, above.

http://members.tripod.com/~MaryStone/

Website of a contemporary artist who teaches basket weaving using

traditional materials (honeysuckle) and designs.

http://www.flickr.com/photos/cherokeebasketweaver/

Some examples of weavers at work.

http://cherokeebasketdesigns.blogspot.com/

A blog with some schematic drawings of traditional basket designs

which helps the viewer understand the basic element in repetitive

designs.

http://cherokeebasketweaversassociation.org/Cherokee_Living_Treasure_Ba.php

The entire site represents the Cherokee Basket Weavers’ Association.

In particular the work of Bessie Russell, cited above by Mary Jo

Watson, is discussed and illustrated.

Pottery

http://rla.unc.edu/Research/CherPot.html

The University of North Carolina has engaged in a Cherokee Pottery

Revitalization project, looking to recover and reproduce pottery

of the 1500-1900 era.

http://www.clayhound.us/gallery/117.htm

Anna Belle Sixkiller Mitchell website.

http://www.runfreeart.com/

A site for Crystal Hanna, potter. See also the Cherokee Artists

Association website above.

http://www.janeosti.com/index.htm

A site for Jane Osti, potter.

http://www.cherokeeheritage.org/Default.aspx?tabid=471 A brief article

through the Cherokee Heritage Center on Victoria Mitchell (Vazquez’s)

selection as a visiting artist to the Native American Museum of

the Smithsonian.

http://www.indiancraftsales.com/Templates/frmTemplateM.asp?CatalogID=135&Zoom=Yes&SubFolderId=19

An example of Victoria Mitchell’s work.

Carving/Sculpture

http://www.willardstonemuseum.com

Perhaps the most famous of all the Cherokee woodcarvers, perhaps

artists. Visit the other sites, as well, to see some of his world-reknowned

works.

http://www.shopoklahoma.com/willards.htm

http://clinton4.nara.gov/WH/Tours/Garden_Exhibit6/stone.html

Be sure to see this piece, displayed in the White House.

Painting

http://www.rsu.edu/faculty/semmons/Native%20American%20Art.htm

Among many images from Native Americans, one painting of Cecil Dick’s

is displayed.

http://waynecountyartsalliance.org/artists/artist.php?f=hill-joan

Wayne County Arts Alliance: one painting, two prints by Joan Hill

displayed.

http://www.cherokeeswestern.com/

Twin Territories is a gallery which frequently has for sale the

work of Cecil Dick and Joan Hill. Thus, viewers may gather some

idea of the styles of both artists by viewing this website.

http://www.3hawkstrade.com/dsprints.html

Three-Hawks Trading Company gallery displaying four images of Dorothy

Sullivan’s work, including a Best in Show in 1994 at the Cherokee

Heritage Center’s Trail of Tears art exhibit, which shows

the Seven Symbols of the Clans.

Bibliography

Adair, James.

History of the American Indians. New York: Promontory Press,

1986.

Bernstein, Bruce.

The Language of Native American Baskets. Washington: Smithsonian

Institute, 2003.

Conley, Robert

J. The Cherokee Nation A History Albuquerque: University

of New Mexico Press, 2005.

Gibson, Arrell

M. The Oklahoma Story. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press,

1978.

Hamilton, Margaret

W. And Sophie I. Stone. Willard Stone Sculptor-Philosopher.

Edmond, Oklahoma: Presimmon Publications, 1993.

Hill, Sarah

H. Weaving New Worlds Chapel Hill and London. The University

of North Carolina Press, 1997.

Hudson, Charles.

The Southeastern Indians. Nashville: The University of

Tennessee Press, 1970

Leftwich, Rodney

L. Arts and Crafts of the Cherokee. Cherokee, North Carolina:

Cherokee Publications, 1970.

Mooney, James.

Myths of the Cherokee New York: Dover Publications, 1995.

Theda Perdue.

Cherokee Women. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press,

1998.

Power Susan

C. Early Art of the Southeastern Indians. Athens: The University

of Georgia Press, 2004.

Thornton, Russell.

The Cherokees: A Population History. Lincoln: University

of Nebraska Press,

1990.

Swanton, John

R. The Indians of the Southeastern United States. Washington

D.C. Smithsonian Institution Press, 1979.

|